|

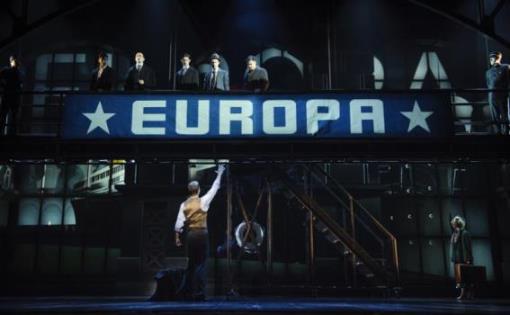

A year ago, I wrote here about a wonderful musical I’d seen 16 years earlier in its 1997 world premiere tryout at the La Jolla Playhouse in San Diego. The show, Harmony, was written by Barry Manilow and Bruce Sussman, and took on a challenging, fascinating subject. It concerned the real-life Comedian Harmonistes, a hugely popular close-harmony singing and comedy group of mixed religion in Germany during the 1920s into the 1930s, whose existence was threatened as Nazi rule was taking over the country. Not without flaws, understandable for a first tryout, the musical was nonetheless terrific, with a thoughtful, involving book and lyrics, and rich, evocative music score, and looked to have a big life ahead. But things don’t always happen the way we expect, and Harmony never made it to Broadway, or even had subsequent productions. I didn’t know why, but felt that something that good deserved to be at least be known, so I wrote about it. To my huge surprise, a few months after writing my article, I was contacted by the Alliance Theatre in Atlanta (a Tony Award-winner for Best Regional Theater) to say that they were reviving Harmony. And that it was doing so in conjunction with the highly-regarded Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles. The finally-revived Harmony had a very successful re-opening. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution headlined its review, “Manilow’s Harmony is a glorious work of art.” Critic Wendell Brock wrote that, “In the end, ‘Harmony’ is a nearly flawless work of art that almost manages to cloak the harrowing underside of history in a bubble of elegance, sophistication and wit. At the end of the night, the waltz fades away, but the stars never dim.” I must admit, it was nice to have my memory vindicated, as well as effort to bring attention to something so good which I’d been telling people about to skeptical looks for almost two decades. It really was that good. Next stop for Harmony, then, would be Los Angeles, and the show opens there on March 4. The result of all this is that I had the chance to talk with the show’s creators, Barry Manilow and Bruce Sussman. What interested me most was the show from the perspective of having seen it – its history and artistic construction. And how it may have changed in the intervening years. In short, how in the world it got from there to here in just, at this point now, 17 years. Photo credit: Greg Mooney And that begins with a simple, nagging thought since that day long ago in San Diego. Their never having written a stage musical before, and in the midst of a hugely successful pop music partnership – how in the world did they come across this unlikely story – one inherently filled with singing and comedy, and even romance, but also much harrowing darkness against the bleakest of backdrops, and what was it that cried out that this, with all its challenges, was the one to do? “Bruce saw a documentary on the Comedian Harmonists,” Barry Manilow recalls, “and he was out of his mind about it. We’d been looking for something all these years. And he was so excited about it. He said to me, ‘Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah’ (and yes, that’s how Manilow laughingly describes his writing partner’s explosive, bubbling enthusiasm. His amusing point coming across that when you work with someone and they are that enthused about something, the enthusiasm is sometimes all you need.) “And I said, ‘Okay.’” As big a leap as it might seem, to go from pop music into writing for Broadway, it turns out that it really wasn’t. In fact, it was that very interest that initially drew the two together years ago. “When we first met in the Calvin Coolidge administration,” Bruce Sussman jokes about their long-term collaboration, it wasn’t to do pop music at all – “we wanted to write musicals.” “I always wanted to get into writing musicals,” Manilow reiterates. “I thought that that was what I would do, write shows. Conduct musicals, be in the theater. I thought I was a theater writer.” Manilow’s interest didn’t immediately translate with Sussman. It was one thing to appreciate the field, but taking the next step was something else entirely. “I didn’t know about writing this. The first time he asked me, I actually said, ‘No.’ I didn’t know how.” What changed is that in 1970, the musical Company by Stephen Sondheim with a book by George Furth opened. It was different from the type of show Broadway was used to – in its edgy score, pointed and episodic book, and inventive staging. And it galvanized the two writers. “Both of us had seen Company,” Sussman recalls. “Everyone around us saw Company. Everything stopped. We all went, ‘Okay, we have to do this.’” The problem though was one of time – and more surprisingly, of unexpected success. Much as the two now wanted to write a musical, and knew precisely the sort of material they now wanted write, “It takes a lot of time to write a musical,” Manilow relates. “It can take five years. Because my career exploded, though, I just never had the time. I didn’t have time until 1992.” To be clear, not writing a show was never for lack of interest or even opportunity. “ People offered us shows to do,” he continues, “but they never spoke to us. Steven Sondheim told me that if you’re going to write a musical and spend all that time, it has to be something you love, that you want to spend all that time with.” “And nothing interested us enough,” Sussman adds. “So, we just waited. And then this project came along.” Among the things that stood out about seeing Harmony back in San Diego is that the songs did not sound like a “Barry Manilow score.” Most composers have their “sound.” Listen to any show by Rodgers and Hammerstein, even an ethnic period piece like The King and I, and you can nonetheless hear Richard Rodgers in it. Something like Cabaret has the flair of John Kander. But listening to Harmony, if someone asked who you thought composed the music, it’s unlikely that you would single out Barry Manilow. Rather than sounding like a jukebox pop show, the score instead evokes the era, as Manilow put aside his comfort zone for the sake of serving the story and its time. As much as that might seem, though, like a specific artistic decision to have avoided what was familiar and comfortable to him, “I did not consciously set out to not write in my comfort area,” he answers – and then pauses a moment to give the suggestion more thought, and continues with a surprising explanation. “Actually, this is my comfort area. Theater. My comfort area is not writing a pop song. With pop songs all you have to go on is ‘I love you, I miss you.’ That’s the whole blank page. “But this was easy. It’s not easy to write a musical, I don’t mean that, but the songs in a musical have a story they fit in, a context. If you put a chair in front of me, I could write a song about what that chair is. But to write a pop song, and find a new way to say, ‘I love you, I miss you’ – that’s torture.” Though the two men finally had found the story they wanted to tell, and were filled with enthusiasm for it, there still was that whole issue of time. Not about finding the time, but taking the time to get things right. “I did three years of research before I even started to write the show,” Sussman states. “And Barry came back from a tour, and he had all these suitcases full of material, songs from the 1930s he’d collected. We did a great deal of research.” It didn’t occur to them to work any other way, since it’s how they always worked. “If I was to write a song about China,” Manilow says, “I would have studied it and researched it.” What they ended up with was a score for Harmony that stands separate and unique from the Manilow-Sussman collection, and for many years Manilow wouldn’t even perform any of its songs in his concerts. They weren’t “Barry Manilow songs,” they were Harmony. As the years passed, he finally did record an album with several of the songs from both Harmony and his other musical with Sussman, Copacabana. And one song from Harmony at last made it into his concerts, the beautiful, “Every Single Day.” (Although now a part of the concert opus -- though this performance below is from a PBS special on Broadway -- you can tell Manilow’s affection to the song. More than just singing it, he almost throws himself into the number, as if acting it from the show.) Clearly, his concert performance of the song does sound like it belongs in that pop world. Oddly, though, when seeing Harmony back in 1997, even “Every Single Day,” with a totally different, subtle, resonant arrangement, sounded nothing like a song for a Manilow concert. It fit the moment of the show and the character perfectly. So, I was curious how audiences of the musical react when what is now “The Big Hit Song” starts up. “We don’t ‘pop’ up the arrangement of ‘Every Single Day,’ explains Manilow. “In fact, we do some interesting things with it, and at first the audience doesn’t even realize it’s That Song. People are so engrossed in the show, in what’s going on in the scene. And it sneaks up on them before they recognize it. By the time the song is over, though, audiences have been going wild.” Which brings us to today. And how these two writers got their show back on stage after a mere 17 years. And how they’ve revisited it themselves. My recollection from long ago was that the first act of that original production was very strong and tight and rich with story, extremely involving, while the second act, though quite good, was trying to find focus. I was curious if that had been their perception, as well. “That’s interesting what you say about focus,” Sussman laughs. “The first act was an hour and 45 minutes. But even running that long, we never got complaints about length. None. However, we always felt it could be stream-lined, and now it’s only an hour and four minutes.” “In that first production,” adds Manilow, “we threw everything up on stage. We were just trying to find out what worked. We didn’t even think anyone would come down to San Diego to see the show! We just wanted to get it onstage, and work on it.” In the intervening years, though, they two have been able to step back and look at the production with a dispassionate eye, and have indeed kept working on the show. From what they said, it seems that most of the effort has been with the second act – although “We did add major new element in the last scene of the first act,” Sussman explains. “It’s a theatrical device that’s thrilling. In the new second act, though, three songs have been removed, two new songs were added, and we even removed one character.” Because the show is so centered on this group of six men and the powerful, dramatic turns their lives go through, they take up the bulk of the stage time. However, there are still two wonderful roles for women, who the men get involved with. (When I saw it in San Diego, one of those roles was played by Rebecca Luker, then at the start of her already-burgeoning Broadway career. She’s since been nominated for three Tony Awards. Interestingly, also in the cast was Danny Burstein, and the two subsequently married.) I was curious if the limitation of female roles was ever a concern for the writers, to try and expand those stories – or did they feel more compelled to stick to the core story and however the women developed from it.) “The women have been better developed than in the original production,” Sussman acknowledges but then laughs self-effacingly. “You should have seen the original script, though. There were eight women in it. You needed a scorecard to keep track! I even put one of the character’s mother in it. I felt he needed a female relationship to his story.” Needless-to-say, all that got dropped. One of the hurdles that was most intriguing about staging the show is that the real-life Comedian Harmonists were utterly remarkable in their vocal gymnastics. (A recent German film on the group uses recordings of the real group.) So, it seemed like that would be a huge challenge to mounting this musical. The actual Harmonists trained for years to be as pitch-perfect and intricate as they were, not just in their singing, but also comic timing. So, how do you find performers who – while not duplicating the artistry of what the originals did – would be able to sing close harmony so well and have such impeccable stagecraft that audiences would believe and accept that these six men on stage are truly that otherworldly good? “This is a very complicated score for actors to do,” Manilow admits. “On the other hand, it might be a dream come true for them. It’s what they studied their whole lives – singing, dancing, acting, doing harmony, timing, everything -- and they get to do all of it in the show. But you do have to be a real actor-musician. They’re not just singing melody, they’re all singing harmony.” All of which begs the overriding question: how in the world did Manilow and Sussman get here? After 17 years wandering in the desert, what happened?? Not only “what happened” in what had been blocking them – but how were they able to get over that hump that had been in their way for almost two decades. It’s a question that the two men have lived with for a long time. “Every Broadway musical has a big mountain to climb,” Manilow says in a voice dripping with experience. “The issue was never the show. People always loved the show. The problems were always investors, producers, financiers, and we’d be stuck for three years. I don’t want to get into specifics, but when you sign a contract with a producer, it’s for three years. There’s nothing you can do. We spent years going from producer to producer, and it just took so much time.” Eventually, the two men decided to regroup and simply “put the show in the drawer” as Sussman says, for the time being. To not press the issue, but wait until they could get it right. Then last year, taking matters into their own hands, they did something vibrantly uncommon. Without lawyers involved, without agents, without anyone else involved, they themselves alone picked up the phone and called the Alliance Theatre in Atlanta, which they were aware had a very good reputation. Yet it’s far more odd than that. This wasn’t a case of just calling the Alliance Theatre on their own, cutting through all the red tape and going straight to the top through one of their many connections, but rather – “We called the main number of the theatre,” Sussman laughs. “We just called the lobby.” They didn’t know anyone at the Alliance. They just thought it would be a good theatre. Needless-to-say, the operator at the front desk was a bit surprised by the call. (One can only imagine the conversation, “I have Barry Manilow on Line 2…No, really.”) But she eventually was convinced who it was she was talking with and connected the two men with Susan Booth, the artistic director who heads up the theatre. It turns out that the reputation of the show over the years preceded the call, and Ms. Booth was not only aware of the musical, but hopeful. “The first thing she said was, ‘Please tell me it’s about Harmony.’” Booth asked for some time to think about the show, needing to decide what she wanted to do with it, and how the musical might fit in with the Alliance. Given that Manilow and Sussman had waited almost 17 years at that point, waiting a while longer wasn’t a problem. What they didn’t expect was how incredibly short they would have to wait. “One hour later she called back to say they wanted to do it,” Sussman says, his voice still not quite believing it – or quite believing what came next. “And she also gave us a start date.” After roadblocks of 17 years, just picking up the phone and calling the front desk did the trick. In a single hour they not only had an acceptance, but a green light to go ahead. Yet success breeds success, because things only got better. “Six weeks later,” Manilow adds, “we then got a call from the Ahmanson. They’d heard about us working with Alliance, and they wanted to get involved, too.” Photo credit: Greg Mooney As difficult and long as the journey has been with Harmony, Bruce Sussman makes clear that they even consider themselves lucky. “The truth is that if it wasn’t for the spotlight of Barry, we never would have gotten this far. The theater is full of people who struggle for years to get their shows on. We know a dozen people with shows who have been trying this long.” There’s absolutely no scintilla of bitterness or regret or even disappointment in their voices as they talk about the two-decade gestation of their show, and getting it staged at the Alliance, and now the Ahmanson. Only palpable enthusiasm and excitement. “Even though it’s been a rough road, it was something we believed in,” Manilow makes very clear. “That’s why we’ve stuck with it for all these years. We believe in this show. We love it.” And that’s why they went about it now they way they have. Not a huge commercial house on Broadway, but regional theater. “Regional theater is the only way to do it the way you want it done,” he continues, his exuberance and admiration building. “Neither Alliance or the Ahmanson have ever asked us about profits or anything like that. That would never happen in the commercial theater. But we’ve had the chance to do the show the way we want it, to get it right. We’re doing the Harmony we wanted to be.” But what about that Harmony and what they’ve always envisioned? Surely there’s a larger goal ahead. You don’t stick with something this long without having that great end in sight – do you?? Other regional theaters, touring, and…perhaps Broadway? I’d read the two men discount having such thoughts, how that wasn’t in their minds. I admit to being skeptical – how could you not be thinking about what’s next?! – but hearing Manilow enthuse about what they have, right now – and the love of the work they’re doing, right now – he actually makes it all makes sense. It is so clear how much he and Sussman dearly love this show, the show that they’ve worked on for two decades, and are just bursting with pride for what it is. Getting on stage in two such prestigious venues. Not for what it might be, possibly, maybe, one day, perhaps. “If there’s a future to it, great,” Barry Manilow says emphatically. “If people see it and want to take it further, great. But we are not thinking about the future. We are only thinking about this show and getting it right. We’ve had the best time with it. It’s been a thrilling experience. And if it doesn’t get any further, that’s fine. We’ve just had the best time.” Harmony has its second life, re-opening at the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles on March 4. What happens next is in the hands of others. What happens now is in good and appreciative hands.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRobert J. Elisberg is a political commentator, screenwriter, novelist, tech writer and also some other things that I just tend to keep forgetting. Feedspot Badge of Honor

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

|

© Copyright Robert J. Elisberg 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed