|

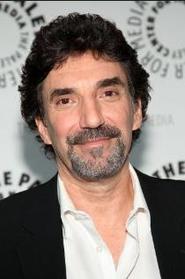

For this week's Email Interview, we have that rarity -- a TV writer you may actually have heard of. This is for two reasons, one of which he's likely pleased with, and the other he could probably do without. The fellow's name is Chuck Lorre. And many people know of him for the whimsical and thoughtful "end cards" he puts after the closing credits of the shows he's created, with his ruminations on various subject. Things in very small print that zip by, but people have gotten to recording on their DVR and then pausing when they pop on. The other is the very public spat he got into with the then-star of his show Two and a Half Men, Charlie Sheen. Alas, this interview was done for the the WGA website long before his more recent -- and highly successful shows -- went on the air. But at least here you don't have to hit "pause" to read what he has to say. Email Interview with Chuck Lorre Edited by Robert J. Elisberg Chuck Lorre has had an extensive and varied writing career. He co-created and executive-produced the series Dharma & Greg; created and executive-produced Cybill, Grace Under Fire and Frannie's Turn; and was co-executive producer on Roseanne. In addition, Lorre was the writer of Debbie Harry's French Kissin' in the U.S.A. and co-writer of the theme and score for the TV series Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. [Subsequent to this interview, Chuck Lorre wrote for CSI, and was on the writing staff of Mike & Molly. He then co-created Two and a Half Men, The Big Bang Theory, and the new series Mom, all of which he also serves as executive producer.] >> Were there any movies, TV shows or books that first got you interested in writing?

CL: The passion, anger and exhilaration that informed the music of the sixties was my first major influence. I was in love with the way music could bypass a lot of the mental censors we carry around. Then everything really changed when I discovered Randy Newman around 1970 or so. This was the first time I'd heard character-driven story-telling with a sharp comedic slant brought to pop music. I was hooked and spent years trying to emulate that approach to songwriting. >> When you write, how do you generally work? CL: Every Dharma & Greg episode is initially written by a group of 4-6 writers. In addition to writing, I act as sort of editor/guide to the process. After many years of banging my head against the wall, I finally admitted that for me, the first draft process never really worked. With the group approach, I have some semblance of control of the script at every point. Also, no one feels they have a first draft to defend, so things move much more quickly. >> Do you have any specific kind of music playing or prefer silence? CL: No music, but if you can't write amidst a healthy dollop of chaos, I don't think you can work on a sitcom. >> Are you a good procrastinator? I put off this interview for three months, what do you think? But when doing a show, the big, scary train of production keeps me from screwing around too much. >> What sort of characters interest you? CL: For me, main characters have to be extraordinary in some way, even if they're extraordinarily dull. Supporting characters must have a life outside of and prior to the story. That way they bring something to the process and are not mere story props or situation catalysts. >> What sort of stories? CL: The story must be about something. Jokes and comedic scenes are obviously essential, but ultimately the story must have a spine, a theme, something you can keep an eye on to determine if you've gone off the track. It could be very simple or very complex, but I find that if you can't explain the hero's journey in simple terms, you're headed for trouble. In sitcom terms, story trouble generally means you'll be faking your way through the episode by linking jokes together -- something I find extremely hard to do. >> How do you work through parts of a script where you hit a roadblock in the story? CL: If the story presents obstacles which defeat our best efforts, it usually means the story is, for the time being, defective and should be abandoned. Coherent stories generally reveal themselves without a lot of heartache. The process still takes several days, but no one has an aneurysm along the way. >> On those occasions when you do hit a roadblock, do you have any specific tricks to help, or just tough it out? CL: One trick is to try and see the story through the eyes of the characters. How would they react? What would they do or say? What do they want? This seems to free up the thought process a bit. But my best trick is simply to hire really smart people and hope they can fix the stuff I'm too dull to figure out. >> When you create a series, at what point do you feel comfortable turning over your creation to others so that it can move in different directions, or do you feel it more important to stay fully involved since you know it best? CL: With Grace Under Fire, Cybill and Dharma I've been very hands on. Some might say obsessively so. Okay, screw it, I'm a control freak and I need help. But.... I am fortunate on D & G to have an incredible staff, so the turning over process is one I'm slowly becoming more comfortable with. It's actually quite a joy to see great work being done that I have nothing to do with. >> What is your most memorable experience as a writer? CL: The first episode of Roseanne I was involved with. I was standing on the stage watching a run-through, and I looked at Bob Myer (the exec) and we shared a wonderful moment of disbelief that these big stars were actually saying the words we wrote. Of course that was probably the only good moment in two years, but it still shines brightly. But the best would have to be the night of the taping of the Dharma & Greg pilot. It was so stunningly clear that we had somehow put together something extraordinary. There was never any doubt in my mind, or I think anyone else's, that we had created a hit show and that Jenna and Thomas would become big stars. >> Was there any particular writer who acted as a sort of mentor to you? CL: That would have to be Bob Myer. He was very patient with me in my wilder days. VERY PATIENT. He also taught me to be patient with writing. To believe that good material would come if you don't quit on the process. If you have a so-so joke, keep hammering away at it until you are convinced you have gold. Don't bullshit yourself by saying the actors will make a mediocre line work. Or the audience will buy it. Also, he showed me how good a show can be if the exec gets his ego out of the way, surrounds himself with good writers and trusts them. In my humble estimation, that was why years 3 and 4 of Roseanne were the best years of the series. >> Why do you write? CL: I can't hit a curve ball and Bruce Springsteen doesn't need a third guitarist.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRobert J. Elisberg is a political commentator, screenwriter, novelist, tech writer and also some other things that I just tend to keep forgetting. Feedspot Badge of Honor

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

|

© Copyright Robert J. Elisberg 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed